Critical retirement choices

18 September 2019

Retirement is a significant life transition that requires careful consideration and planning. Making critical retirement choices can have a profound impact on your financial stability and overall well-being in your golden years.

Setting Retirement Goals

Before diving into the details, it’s crucial to establish clear retirement goals. Consider factors such as lifestyle expectations, travel plans, healthcare needs, and any other personal aspirations. Setting realistic and measurable goals will serve as a foundation for making informed decisions.

Financial Planning

- Budgeting: Assess your current financial situation and create a realistic budget. Understand your income, expenses, and potential sources of retirement income, such as Social Security, pensions, or investment returns.

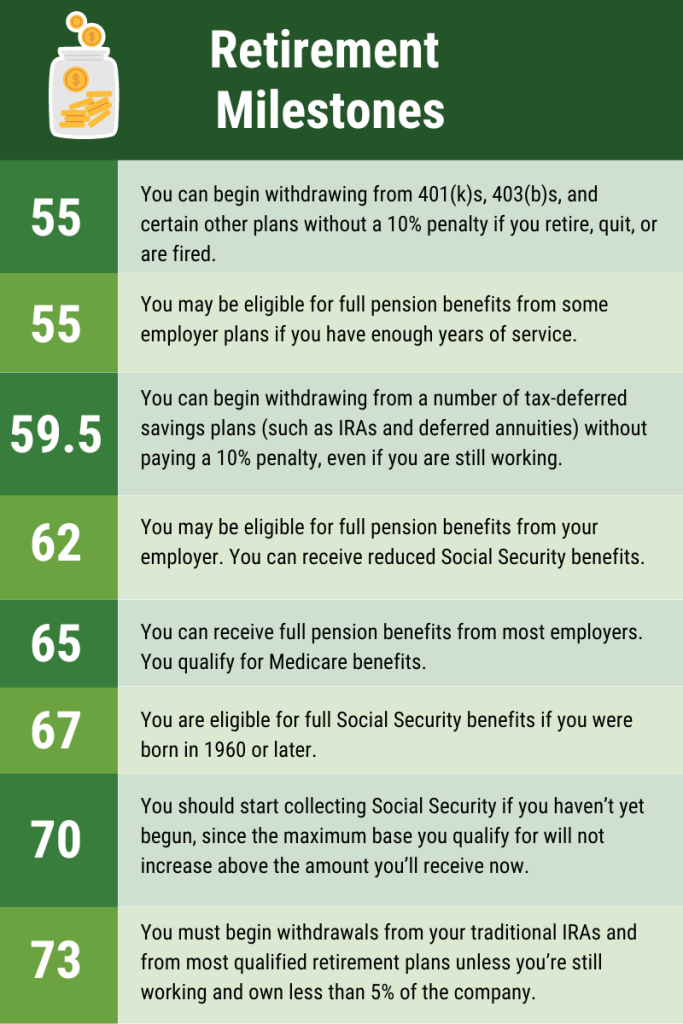

- Savings: Start saving early and consistently. Leverage retirement accounts like 401(k)s, IRAs, or other employer-sponsored plans. Take advantage of employer matching contributions and explore additional investment options to maximize your savings.

- Debt Management: Address outstanding debts before retirement. Reducing or eliminating high-interest debts can significantly improve your financial stability during retirement.

Healthcare Planning

- Insurance: Review your health insurance options, including Medicare and supplemental plans. Understand coverage, costs, and any gaps in your insurance to ensure adequate healthcare during retirement.

- Long-Term Care: Consider long-term care insurance to protect against potential healthcare expenses. Planning for the possibility of needing assistance in later years is a critical aspect of retirement preparation.

Housing Considerations

- Downsizing: Consider your current housing and what your needs will be in the future. Selling a larger home can free up equity and reduce ongoing expenses.

- Location: Explore different locations for retirement living. Some areas may offer a lower cost of living, better healthcare options, or a climate more suitable to your preferences.

Estate Planning

- Wills and Trusts: Draft or update your will and establish any necessary trusts. Clearly outline your wishes for the distribution of assets and consider factors such as estate taxes.

- Power of Attorney: Designate a power of attorney for financial and healthcare decisions. This ensures that someone you trust can manage your affairs if you become unable to do so.

Preparing for retirement involves a combination of thoughtful decision-making and strategic planning. By addressing critical retirement choices early on, you can enhance your financial security and enjoy a fulfilling retirement lifestyle. Consulting with financial advisors and professionals in various fields can provide valuable insights tailored to your unique situation, ultimately paving the way for a comfortable and enjoyable retirement.

See Related Posts

popular articles

Categories

2

Today’s update

New Posts

blog read